Her exhibition Thicker than Water, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 2018, investigated the notion of survival, hope, and parenthood in similar ways to Yu’s novel. A parent, Imady has exhibited work that draws on stories she recorded from families who left Syria as refugees. The novel also bears some resemblance to the mixed media work of Syrian American artist Essma Imady.

Like Mansour’s compelling drama, Yu captures the playfulness in her young characters, even when they are acting out, practicing their new English swear words, and losing patience with each other. Ifrah Mansour’s one-woman play, How to Have Fun in a Civil War, for example, takes place during the Civil War of Somalia, where the young Ifrah plays and dreams and seeks love just like any child. In this way, the novel bears similarities to other works by artists from refugee communities. As a child, Firuzeh has whimsical fantasies, a belief in the magical, and a longing for stability, connection, and a place to call home. Yu never lets the reader lose sight of the youthfulness of her protagonist. Amid horrific displays of mistreatment, disastrous run-ins with nature, and a sadness that threatens to swallow them whole, the book offers depictions of tenderness and the fierce love a family has for one another. Fleeing wartorn Kabul, Afghanistan, the Daizangis endure deadly ocean squalls, inhumane treatment in a detention center off the coast of Australia, and further degradation once they reach Melbourne, as the children attend school and the parents seek work. The glimmers of joy experienced by the asylum seekers - who include young Firuzeh Daizangi, a 10-year-old when she arrives in Australia her little brother Nour and their Abay and Atay (mom and dad) - are often upstaged by the traumatic experiences of the family’s triumphant and tragic journey. Later, she reflects with Sister Margaret, saying, “I asked the wrong questions, didn’t I?” The nun responds that she, personally, would ask the detainees about joy: “When you have nothing and no reason to hope, when the odds are impossible and not one but two governments stand against you, how do you laugh? How do you see beauty? How do you still show kindness and love?”

The writer spends the day peppering detention center inmates with questions about the conditions they have endured. The writer is given a tour by Sister Margaret, a nun and a tireless advocate for refugee families - including the Daizangi family, whose story forms the center of the novel.

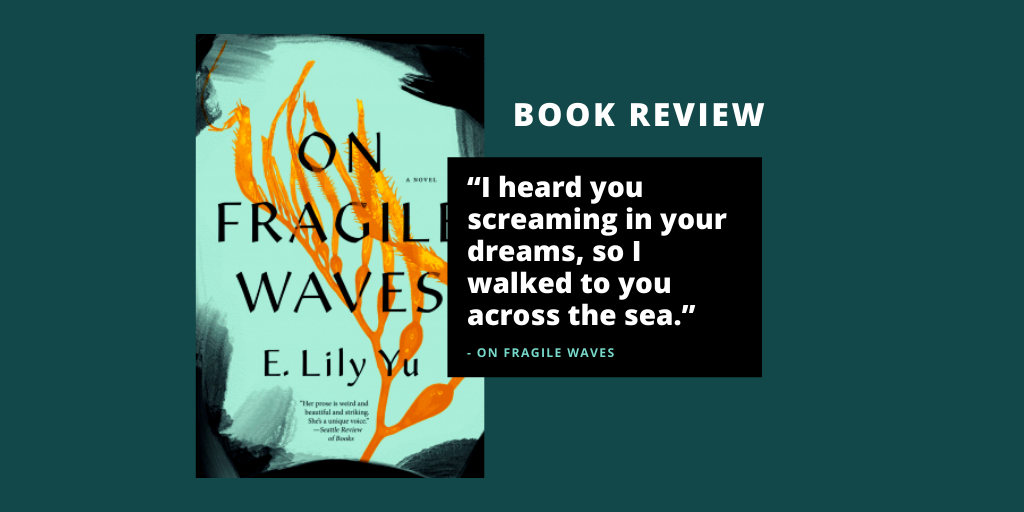

A character Yu calls “the writer” has traveled to Australia to interview asylum seekers in the Afghan migrant community there and to visit detention centers as part of her research. Lily Yu’s disquieting debut novel On Fragile Waves offers a kind of authorial self-critique regarding the representation of diasporic migrants.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)